Jim suggested starting this type of activity by answering an "analysis question," one that asks students to "examine and break information into parts by identifying motives or causes" and to "make inferences and find evidence to support generalizations." Key words, according to the handy Bloom's Taxonomy flip book I keep at my desk include "analyze, compare, dissect, inspect, categorize, contrast, motive, discover, examine." To get students to engage in analysis, that same book suggests posing questions like "What conclusions can you draw," "what's the relationship between," "what motive is there," "why do you think"...

Jim also suggested using a relatively short section of the textbook for this exercise, rather than an entire chapter. Here's a sample assignment I created based on the idea, using the section "The Dawes Act: Allotments Subdivide the Reservations," from Chapter 11 of Montana: Stories of the Land.)

Using the text (including sidebar quotations, posters, image captions, etc.), on pages 219-222 of Montana: Stories of the Land, create a found poem that answers the following question: What conclusions can you draw about the policy of allotment?

I tried the activity myself just to see if it would work and one thing I noticed is that to write my found poem I had to reread the pages several times; this repeated exposure to the text reinforced my understanding of the topic and my ability to recall specific details.

This isn't the first time we've suggested poetry activities; asking students to write poems about history or using historical sources has the benefit of encouraging close reading, analysis, and a better understanding of perspective and point of view.

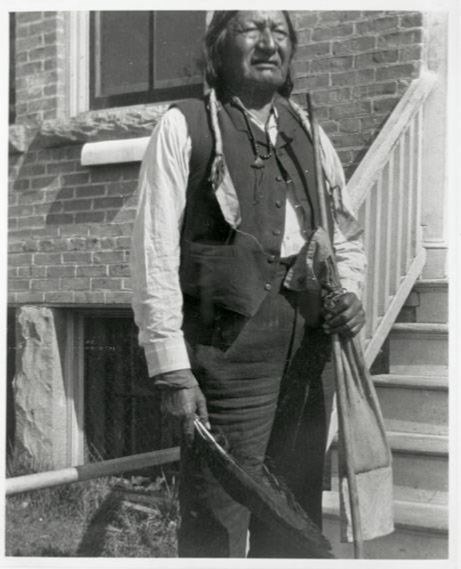

I talked about "Poems for Two Voices" in a post some time back, after which Billings librarians Kathi Hoyt and Ruth Ferris created a lesson plan using the technique and excerpts from speeches by Crow chief Plenty Coups and Lakota chief Sitting Bull.

Ruth is also the person who first introduced me to found poetry--she wrote a lesson plan for using it with historic newspapers (particularly with Montana's first newspaper, the Montana Post). You can find that lesson on page 23 of the Girl from the Gulches: The Story of Mary Ronan Study Guide.

“An Artist’s Journey: Transform a Painting into Poetry” (grades 1–7) asks students to examine several Russell paintings using their five senses, before choosing one painting to use as an inspiration for a poem. (If you teach at a Montana public school, your school library should have received the Montana's Charlie Russell teaching packets we created, of which this lesson is a part; we also posted all of the material in packets on our website).

Biographical Poems Celebrating Amazing Montana Women Lesson Plan (Designed for grades 4-6) asks students to research specific Montana women (by reading biographical essays) and to use the information they gather to create biographical poems. Through their research (and by hearing their classmates’ poems) they will recognize that there is no single “woman’s experience,” women’s lives are diverse, and that people can make a difference in their communities.

What's your experience with integrating poetry and social studies? Let me know and I'll share it with the group.

P.S. Don't forget to sign up for Making It Real: A Workshop for Elementary and Middle School Teachers, to be held on June 24, 8:30 a.m.-3:30 p.m. at the Montana Historical Society in Helena. Learn more about this workshop, then register to attend this exciting professional development opportunity (6 OPI Renewal Units available).